A MUSEUM TOOK MY ART. THIS IS WHAT IT TAUGHT ME

There are parts of being an artist we celebrate openly. Exhibitions. Commissions. Positive feedback. Being chosen. What we talk about far less are the quiet breakdowns, the moments where things don’t collapse dramatically but instead dissolve through missed signatures, vague assurances, and systems that rely more on trust than accountability.

Afrofuturism has always been one of the most compelling art forms to me. Not because it is futuristic, but because it is intentional. Artists like Lina Iris Viktor and writers like Octavia Butler didn’t simply imagine futures, they constructed them with discipline, restraint, and authority. That approach stayed with me, and eventually I felt the pull to explore Afrofuturism in my own way.

I didn’t know where to start. I wasn’t sure how Afrofuturism could live inside my existing practice of oil on wood. The material mattered to me. The surface mattered. The process was messy and required repetition. It took multiple failed attempts to find a visual rhythm that felt right. But once I did, the work began to sharpen.

THE PIECE THAT STAYED WITH ME

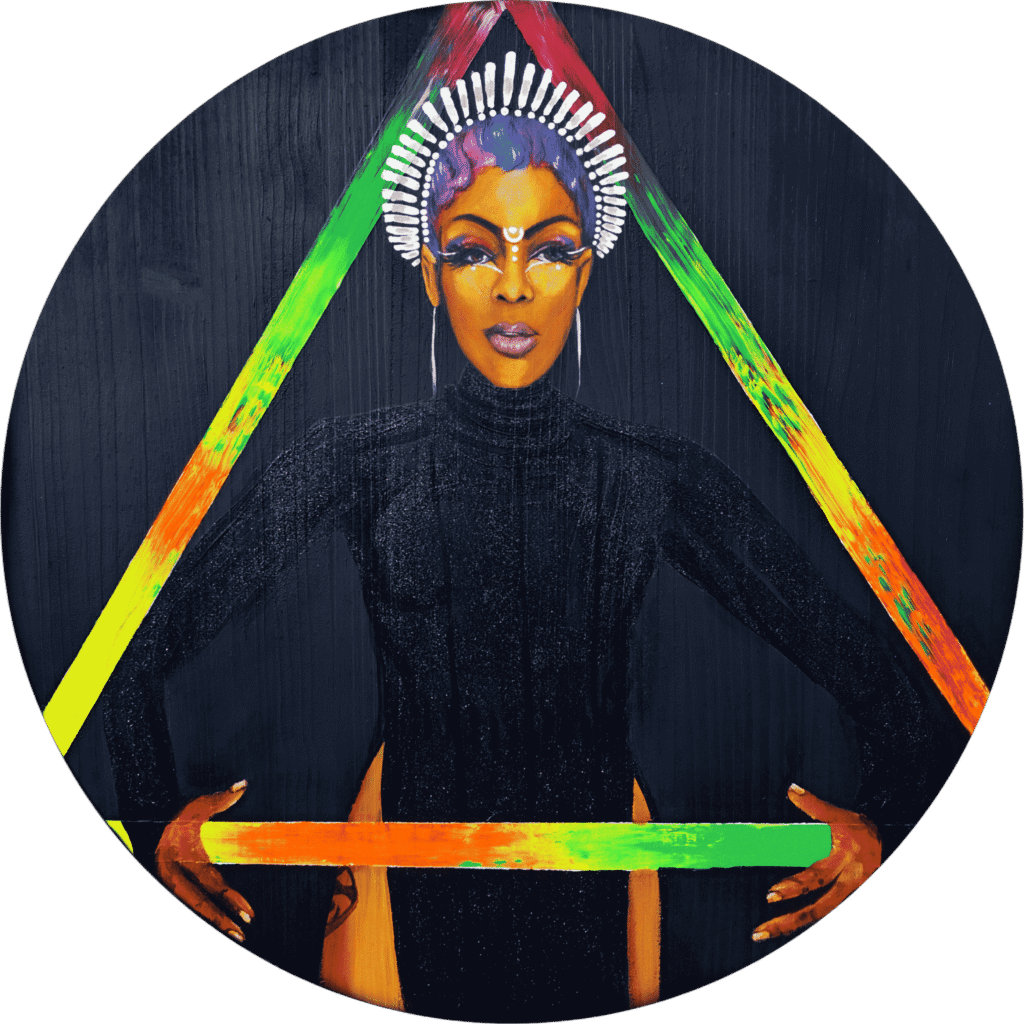

The piece inspired by Iniko was where everything locked into place. That blurred line in the work took countless tries to resolve. When it finally worked, there was no mistaking it. The technique held. The concept held.

Iniko was the right subject at the right moment. She entered culture with force, fast cadence, and language that felt both futuristic and grounded. She didn’t ask for space. She took it. Painting her allowed me to mirror that same energy visually. That work marked the point where Afrofuturism in my practice stopped being an experiment and became a claim.

credit – Iniko / Blog | UrbanNoize

WHY I STEPPED BACK FROM GALLERIES

Around this same period, five of my works were placed with a well known museum in Texas during what was presented as a standard professional exchange. Among them was a commissioned piece tied to a breast cancer awareness initiative. I was told the work received positive feedback and that it would later be displayed at a major hospital in Texas. That installation never happened. I have never seen that piece again.

At the time, the museum appeared established. The owner was personable and familiar. The institution had history. What it did not have was a completed contract. I drafted one in good faith and followed up multiple times. It was never signed. Like many artists balancing travel, exhibitions, and opportunity, I trusted reputation over structure. That trust turned out to be misplaced.

Longevity is not accountability. Familiarity is not protection.

Communication began to slip in ways I’ve since learned to recognize as institutional avoidance. Delayed responses. Circular explanations. Urgency without resolution. I was told the museum was experiencing changes related to its commercial property space. Whether the issue was financial, logistical, or managerial, I will never know. What became clear was that resolution was no longer the priority.

After nearly a year of open communication and flexible timelines, I shifted strategies. I stopped asking and started retrieving. A specific date and timeframe were provided. I traveled several hours, arranged lodging, and arrived at the location with building security present to formally retrieve my work.

The doors were locked. The owner had left early.

At that point, ambiguity ended. I filed a police report and worked directly with a detective who made multiple attempts to contact the museum owner. I visited the police station personally and provided documentation. I shared a PO Box and allowed a thirty day window for the artwork to be returned.

Nothing was returned.

HOW BODY AND FACE PAINTING HELPED ME HEAL

Whether the works were sold, misplaced, or intentionally withheld is unknown. What remains is documentation, absence, and clarity about how easily artists can be left unprotected when structure is missing.

This experience didn’t end my practice. It refined it.

I stepped back from exhibiting temporarily, not because my work lacked value, but because clarity has a way of resetting boundaries. I also stepped back from gallery systems that relied on ambiguity rather than procedure. That pause wasn’t retreat. It was recalibration.

Art found me again in unexpected ways. Body and face painting carried me into symphonies, community spaces, private events, and live performances. These experiences reminded me that art does not belong exclusively to institutions, and that creativity often survives just fine without them.